Old Engli.sh

The Portal to the Language of the Anglo-Saxons

Read another, randomly chosen, past Old-Engli.sh News article:

Loving the Letter L: The Dictionary of Old English Progress Report 2019

December 2020

February 2014

British Library Soon to Digitize its 1000th Manuscript

The British Library has been producing state-of-the-art digitizations of its early manuscripts, many of them containing Anglo-Saxon texts. A newly released list reveals that the institution will soon have reason to celebrate a grand jubilee: it is about to digitize its one thousandth medieval manuscript. |  The logo of the British Library's Medieval Manuscript Blog |

There is hardly any institution in the world that has more experience with data digitization than the British Library. For over two decades, the institution has worked with external partners, large sums of funding money and advanced technology to create one of the largest and most sophisticated mass digitization programmes in existence today. Now, the library’s "Medieval Manuscript Blog" has published a short article, entitled Yet Another Giant List of Digitised Manuscript Hyperlinks, in which a reference is provided to a file containing all the digitized manuscripts produced by the library’s Medieval and Earlier Manuscripts Department to date. The astonishing result: The library has managed to digitize an impressive 920 early manuscripts!

Digital images are now available of some of the library’s most valuable possessions. The database includes fantastic palaeographical treasures, like the Gutenberg Bible, Caxton’s prints, magnificent medieval drawings from the Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts. And of course, several gems written in Old English.

The advantages of publicly accessible digitized manuscript collections are enormous. They open up great possibilities for scholars – philologists and palaeographers alike, and maybe even historical linguists, who may occasionally want to double-check a critical example in their text edition against the manuscript original. The digital images may be used in as of yet unimagined areas of research, reveal illegible or hidden contents, and find applications in educational contexts. The public, likewise, profits from the high-quality digitized images through software like Turning the PagesTM, which allows visitors to marvel at many of a manuscript’s images and writings and not just a single page as traditionally exhibited in a display case. Most important, however, is the library’s commitment to the preservation of unique, rare and fragile heritage items through data digitization. Never again will disasters like the Cottonian Fire in 1731 bereave mankind of its greatest cultural treasures.

Although the British Library will top the 1000 mark on digitized early manuscripts in 2014, this number still represents less than only one percent of its total collection. There is still a lot to be done to preserve mankind’s priceless treasures for posterity.

Digital images are now available of some of the library’s most valuable possessions. The database includes fantastic palaeographical treasures, like the Gutenberg Bible, Caxton’s prints, magnificent medieval drawings from the Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts. And of course, several gems written in Old English.

|

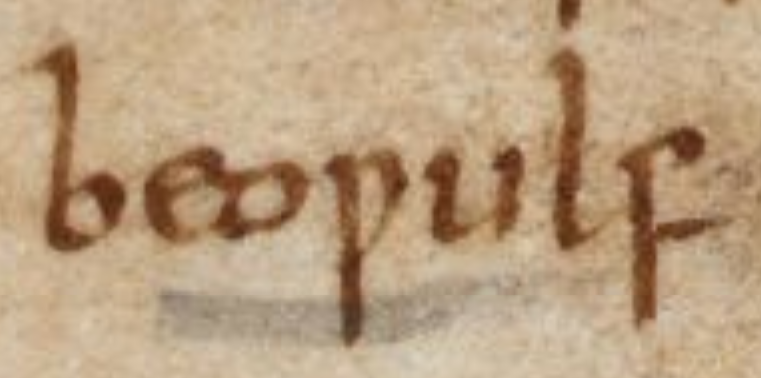

There is manuscript Cotton Vitellius A XV, the only witness of the famous epic Beowulf. The digital images allow zooming in to spectacularly fine detail. You can also check out the beautiful decorations in manuscript Cotton MS Nero D IV, which contain the Lindisfarne Glosses. Or try reading the West-Saxon Gospels, not just in their Anglo-Saxon original, but in the very handwriting of their medieval manuscript, Royal 1 A XIV. |

|

A high-resolution detail image from the Beowulf manuscript, f. 139v |

The advantages of publicly accessible digitized manuscript collections are enormous. They open up great possibilities for scholars – philologists and palaeographers alike, and maybe even historical linguists, who may occasionally want to double-check a critical example in their text edition against the manuscript original. The digital images may be used in as of yet unimagined areas of research, reveal illegible or hidden contents, and find applications in educational contexts. The public, likewise, profits from the high-quality digitized images through software like Turning the PagesTM, which allows visitors to marvel at many of a manuscript’s images and writings and not just a single page as traditionally exhibited in a display case. Most important, however, is the library’s commitment to the preservation of unique, rare and fragile heritage items through data digitization. Never again will disasters like the Cottonian Fire in 1731 bereave mankind of its greatest cultural treasures.

Although the British Library will top the 1000 mark on digitized early manuscripts in 2014, this number still represents less than only one percent of its total collection. There is still a lot to be done to preserve mankind’s priceless treasures for posterity.

- Visit the www.oenewsletter.org